A Brief Summary of Scottish Catholic History

In November 2024, Pope Francis wrote that the study of Church History is about keeping ‘the flame of collective memory alive, so that the faithful can navigate the present with a clearer sense of perspective, rooted in the Church’s lived experience across the centuries’. In the Jubilee Year 2025, the National Heritage Commission, invites us to look back over the story of the Faith in our country.

The life on earth of Our Lord Jesus Christ is the central event of human history. “The Word who is Life: this is our subject"(1 John 1:1). Anything before was leading up to it; nothing after will compare “until he comes again” at his Second Coming. Church History is about how well we have followed The Lord, and also how badly, down through the centuries.

The Gospels tell us about the Lord’s Birth, his teaching and his miracles, his Crucifixion, Death and Resurrection, and his Ascension into Heaven. The Book of The Acts of the Apostles records the coming of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles at Pentecost and how they were willingly propelled out across the face of the known earth to bring the message of Christ to the furthest corners.

Saint Peter

eventually settled in Rome where he was martyred for the Faith about 65 AD. He was hurriedly buried on the Vatican Hill where today Saint Peter’s Basilica stands over the resting place of his bones. He was the ‘Rock’ on which Our Lord built the Church (Matthew 16:18), on which it could lean and depend, and his successors, the Popes down through the centuries, have inherited that role, including our present Holy Father, Pope Francis. We Scots Catholics have always been known for, and have always prided ourselves on, our loyalty to the Pope in every age.

None of the Apostles reached Scotland. The Christian Faith was brought by people for whom we have no names. The first name we have in our story is

Saint Ninian of Galloway

who belonged to a Christian family and went to Rome ‘to find out more about the Tradition’ in the time-honoured phrase. He was consecrated Bishop for Scotland in Rome in 394 by Pope Saint Siricius. He made his base at Whithorn.

Saint Mungo

, first Bishop of Glasgow, was born in 518, and

Saint Columba

came from Donegal in 563. These are the three great pioneers of our Scottish Catholic story. Earlier centuries are shrouded in the mists of history and historians will dispute over dates. The above are the traditional ones. A succession of holy men and women built on the early foundations until Scottish monarchs themselves began to take a lead.

Saint Margaret

, (1045-93), Queen of Scots, married to King Malcolm Canmore in 1070, strengthened the links between Scotland and Rome and encouraged the monastic orders to come to Scotland. Her policies were continued by her sons, especially Saint David, King of Scots, and many of his successors until Mary Queen of Scots (1542-87). Our land is dotted with evocative monastic ruins such as at Melrose, a Cistercian foundation. The orders of canons and friars also came to Scotland and the latter are still remembered in street names like Whitefriars (Carmelites), Blackfriars (Dominicans), Greyfriars (Franciscans). A Scottish ‘export’ from those days was

Blessed John Duns Scotus

(1266-1308), a Franciscan friar, who taught in the universities of Oxford, Paris and Cologne. Known as ‘Doctor Subtilis’, he is recognised as one of the foremost thinkers of the late Middle Ages. He was a strong supporter of the popular devotion to Our Lady’s Immaculate Conception long before it was formally defined as a doctrine of the Church in 1854.

On 30 April 1175, Bishop Jocelin acquired for Glasgow from Pope Alexander III the title

Specialis Filia Romanae Ecclesiae (

Special Daughter of the Roman Church

). Later, this title was extended to the whole of Scotland and reiterated 800 years later by Pope Saint John Paul II on his visit in 1982, at the biggest gathering of Scots in our nation’s history, when 300,000 celebrated Mass with him at Bellahouston Park in Glasgow.

The Declaration of Arbroath, in 1320

, which declared Saint Andrew to be Scotland’s long-standing patron, appealed to the Pope to recognise Scotland as a separate nation. Several popes confirmed Scottish Nationhood in the years that followed. The Vatican is one of the few international bodies today which respects the distinctiveness of Scotland, recognising, for example, that our Bishops’ Conference is separate from England and Wales.

The Reformation Parliament of 1560

marked the most serious rupture in the story of Scotland. It forbade the celebration of Mass in Scotland; priests were not allowed to be in the country at all; parents were forbidden to pass on the Faith to their children; pilgrimages to holy places were banned. A whole way of life that had united the country was swept aside almost overnight and those who wished to remain faithful to the Mass and the Pope continued to practise their faith secretly, running the risk of severe penalties. Still, the Southern Hebrides, the Western Highlands and Galloway were places where people held on tenaciously to the Faith through 250 years of persecution. The Enzie, a small area in the north-east, provided a disproportionately high number of priests to serve the Church over generations including the influx of Irish immigrants in the 1800s.

One figure standing out from that time is

Saint John Ogilvie

, Jesuit priest and martyr, who was put to death in Glasgow in 1615 for upholding the authority of the Pope to lead us in matters of Faith. He had been trained on the continent of Europe. Several colleges were set up there, in Rome, Spain, France and Bavaria to provide priests for Scotland. Still today we have two seminaries abroad: the

Pontifical Scots College, Rome

, and the

Royal Scots College, Salamanca

.

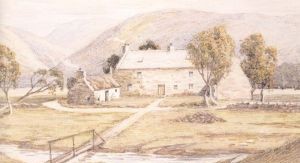

In time, with considerable courage, colleges were established secretly in Scotland, in remote locations and under primitive conditions,

Loch Morar

in the Western Highlands and

Scalan

in the Braes of Glenlivet being the best known. Both suffered at the hands of government soldiers after the Jacobite uprisings of the 1700s. Our support for these held us back several decades in re-gaining our freedoms. Important names at this time were Bishops Thomas Nicolson, Hugh MacDonald, George Hay and John Geddes (who met and corresponded with Robert Burns). They were known, with others, as the

Vicars Apostolic

. Another feature of those times was a small but resilient Catholic aristocracy whose houses, like Traquair near Innerleithen, supported local Catholics and were refuges for priests travelling from one isolated Catholic community to another. In freer times some of them financed the building of new churches.

Eventually we regained most of our freedoms in the

Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829

. Gradually the Church began to grow again. It was strengthened by immigration from Ireland, and added to this figure were large numbers from Italy, Poland, Lithuania, the Ukraine, India, parts of Africa and other countries, including the last few years, as well as movement within Scotland from the country to the towns and cities. Six dioceses were set up in 1878, the first act of Pope Leo XIII and, with huge expansion between the two World Wars, two further dioceses, Motherwell and Paisley, were erected in 1947.

Education has been a recurring theme

throughout the centuries. In the 15th century, the Church established the universities of St Andrews (1413), Glasgow (1451) and Aberdeen (1495). In the days of persecution, it was always difficult to finance teachers and resources. In the 1800s, religious orders of men and women started Catholic schools, often coupled with combatting poverty. They were helped in this by groups run by ordinary Catholics such as the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul, founded in Paris in 1833 and established in Edinburgh in 1845.

In 1872, the government obliged parents to send their children to school, but these were places where the presbyterian faith would be taught, so Catholic parents wanted schools of their own. Central Government subsidised these, but local government would only support their own schools, so Catholic schools suffered a lack of resources and the loss of teachers who could not bring up their own families on the meagre wages. There were teachers who felt it was their vocation to remain unmarried to support the Catholic schools. By means of the

Education Act of 1918

, some people in government who had the spirit of being public servants, recognised that this was unjust, and arranged to have the Catholic schools brought into the state system while genuinely providing safeguards for the continued teaching of the Catholic Faith within them. This points to one aspect of our story we should never forget – how we were often helped from the most unlikely of quarters as people of other faiths helped us with land, property and finance, out of a sense of decency and a desire to create a more harmonious society.

The Second Vatican Council

(1962-65) introduced major changes in the life of the Catholic community:

- The Mass began to be celebrated in our own language, not Latin, and a greater participation in it was encouraged by all present, with a renewed love for Sacred Scripture.

- A new word appeared: Ecumenism. Catholics were encouraged to forgive the past, and to forge new and strong ties with the members of other Christian Churches.

- Similar relations were to be fostered with believers of other religions.

- A fresher image of the Church was presented as the People of God on pilgrimage together to Heaven through this life, supporting one another, and playing an active part in the wider society whose ‘joys and hopes, fears and anxieties’ are often ours too, in this way building up the Kingdom of Christ on this earth.

- All of these new approaches would help us to answer another call from the Council, for each of us to pursue holiness of life, so that we might become, each of us, ‘the saints of the 21st century’, as Pope Benedict encouraged our young people during his visit in 2010.

If Saints Ninian, Mungo and Columba walked into any of our churches today during the celebration of Mass, they might have difficulty with some of the outward forms and the language, but within seconds they would know we were celebrating the same Mass with the same beliefs that they had brought us centuries ago.

If you would like further reading, please click on the links embedded above (mostly Wikipedia articles), or key into your computer search engines some of the names and places mentioned in the text above.